“THE FRENCHTEK OF 1518” a literary-remix

by Sonic Belligeranza 28 Marzo 2018THE FRENCHTEK OF 1518

This text is a literary remix of an article by Ned-Pennant Rea*1 interspersed with urban myths, rumors, gothic horrors, lies and madness from oral history of Rave in Italy. The additions to the original text conjured by a round table of Tekno knights are presented here in green and between [brackets]

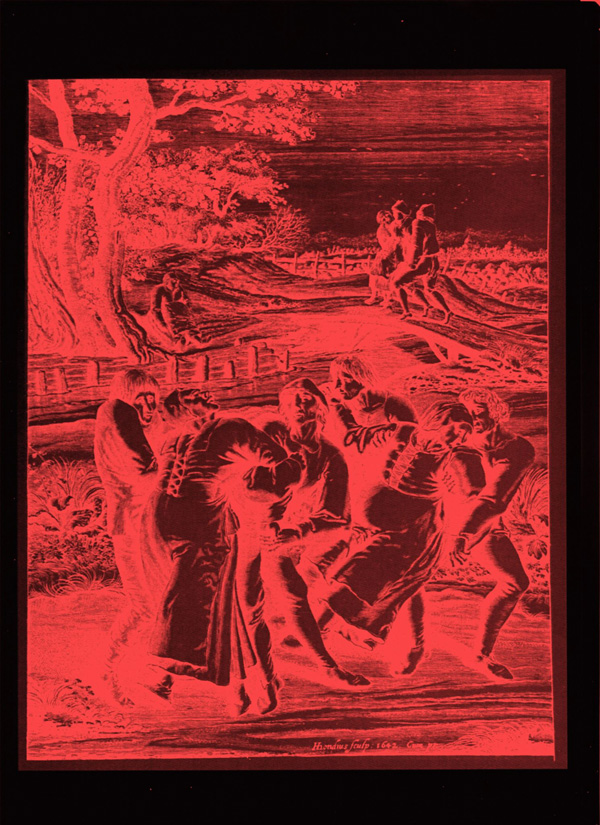

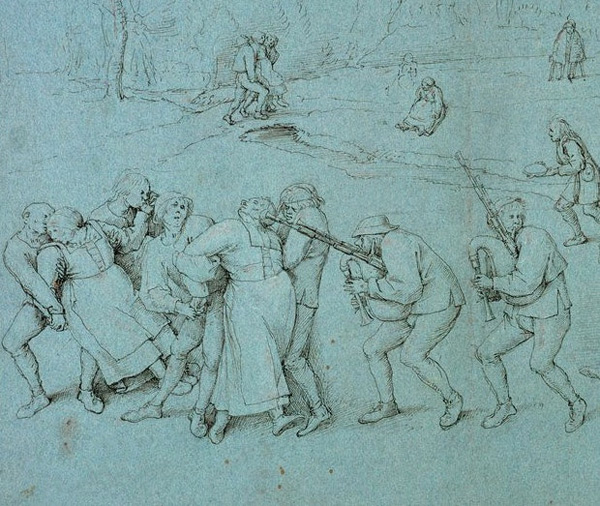

In full view of the public, this is the apogee of the choreomania that tormented Strasbourg for a midsummer month in 1518. Also known as the “dancing plague”, it was the most fatal and best documented of the more than ten such contagions which had broken out along the Rhine and Moselle rivers since 1374. [from Czech Tech, to Japan Teknival, to la Ruta del Bakalao in Spain, Fintech in Italy, Burning Man, Slovtek, etc.). Numerous accounts of the bizarre events that unfolded that summer can be found scattered across various contemporary documents and chronicles compiled in the subsequent decades and centuries. One seventeenth-century chronicle by the Strasbourg jurist Johann Schilter quotes a now lost manuscript poem:

Many hundreds in Strassburg began

To dance and hop, women and men,

In the public market, in alleys and streets,

Day and night; and many of them ate nothing

Until at last the sickness left them.

This affliction was called St Vitus’ dance.*2

In the year 1518 AD … there occurred among men a remarkable and terrible disease called St Vitus’ dance, in which men in their madness began to dance day and night until finally they fell down unconscious and succumbed to death.*3 [Maybe the first death at Fintek has been Selene’s one, a girl who went for a slash in one of the many unguarder electrical closet, when her piss touched a live wire she got instantly electrocutioned] The physician and alchemist Paracelsus visited Strasbourg eight years after the plague and became fascinated by its causes. According to his Opus Paramirum, and various chronicles agree, it all started with one woman. Frau Troffea had started dancing on July 14th on the narrow cobbled street outside her half-timbered home. As far as we can tell she had no musical accompaniment but simply “began to dance”.*4 [ever heard about Silent Rave?] Ignoring her husband’s pleas to cease, she continued for hours, until the sky turned black and she collapsed in a twitching heap of exhaustion. The next morning she was up again on her swollen feet and dancing before thirst and hunger could register. By the third day, people of a great and growing variety — hawkers, porters, beggars, pilgrims, priests, nuns — were drinking in the ungodly spectacle. The mania possessed Frau Troffea for between four and six days, at which point the frightened authorities intervened by sending her in a wagon thirty miles away to Saverne. There she might be cured at the shrine of Vitus, the saint who it was believed had cursed her. But some of those who had witnessed her strange performance had begun to mimic her, and within days more than thirty choreomaniacs were in motion, some so monomaniacally that only death would have the power to intervene.

6 [A crumbling warehouse of incredible dimension, just there at the gates of Rome, left in a state of neglect and abandon. Anywhere in Europe you couldn’t find a disused building complex of such proportions, FINTECH was a former factory specialized in construction industry, located at Corviale borough where the notorious “Serpentone”, a monster building 1 km and half long, was erected as a sort of symbol of Roman suburbs decay. According to local popular urban myth, Mario Fiorentini, the architect responsible for the urban planning, committed suicide troubled by the sense of guilt of having constructed such an hideous and extremely dangerous building complex]

Carpenters and tanners were ordered to transform their guild halls into temporary dance floors, and “set up platforms in the horse market and in the grain market“ in full view of the public. To keep the accursed in motion and so expedite their recovery, dozens of musicians were paid to play drums, fiddles, pipes, and horns, with healthy dancers brought in for further encouragement. The authorities hoped to create the optimal conditions for the dance to exhaust itself.

It backfired horribly. Being more inclined to a supernatural than a medical explanation of the dance, most of the onlookers saw in the frenzied movements a demonstration of the magnitude of Saint Vitus’ fury. None being free of sin, many were lured into the mania. The Imlin family chronicle records that within a month the plague had seized four hundred citizens.*7

If not an angry saint or overheated blood then what did cause the dancing plague? In the view of Paracelsus, Fra Troffea’s marathon jig was a ploy to embarrass Herr Troffea: “In order to make the deception as perfect as possible, and really give the impression of illness, she hopped and sang, which was all most distasteful to her husband.”*11 Upon seeing the success of the trick, other women began dancing to annoy their husbands too, powered on by “free, lewd and impertinent” thoughts. This type of dancing mania was classified by Paracelsus as Chorea lasciva (caused by voluptuous desires, “without fear or respect”), which sat alongsideChorea imaginativa (caused by the imagination, “from rage and swearing”), and Chrorea naturalis (a much milder form, caused by corporal causes) as the three main forms of the condition.*12 While the famously iconoclastic Paracelsus does deserve credit for placing the cause of the disease in the minds of the choreomaniacs rather than in heaven, he was also a misogynist whose diagnosis looks somewhat ridiculous now.

Waller’s explanation of the dancing plague emerges from his deep knowledge of the material, cultural, and spiritual environment of sixteenth-century Strasbourg. He opens his book with a quote from H. C. Erik Midelfort’s A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany (1999):

Madnesses of the past are not petrified entities that can be plucked unchanged from their niches and placed under our modern microscopes. They appear, perhaps, more like jellyfish that collapse and dry up when they are removed from the ambient sea water.*13

According to Waller, the Strasbourg poor were primed for an epidemic of hysterical dancing. First of all, there was precedent. Every European dancing plague between 1374 and 1518 had occurred near Strasbourg, along the western edge of the Holy Roman Empire. Then there were the prevailing conditions. In 1518, a string of bad harvests, political instability, and the arrival of syphilis had induced anguish extreme even by early modern standards. This suffering manifested as hysterical dancing because the citizens believed it could. People can be extraordinarily suggestible and a firm conviction in the vengefulness of Saint Vitus was enough for it to be visited upon them. “The minds of the choreomaniacs were drawn inwards,” writes Waller, “tossed about on the violent seas of their deepest fears.”*14

Of course, the dancing plagues have another parallel — modern rave culture. Though usually without the bloody feet and pleas for mercy of our sixteenth-century choreomaniacs [even though Goa party are thought to be first and foremost homage/invocation of some sort of Hindu deities whatsoever], and often with a little chemical help, it is not uncommon for partygoers to dance for days with little break, forgoing sleep and food, sometimes shifting their feet with poise and balance, and sometimes leaping with none. Should one such reveller — perhaps fuelled by a particularly potent dancefloor potion — be transplanted onto the horse market stage of early modern Strasbourg half a millennium ago, they might not feel entirely out of place.

NOTES:

1. Ned Pennant-Rea is an editor and writer from London. He likes early modern literature and wrote his Master’s thesis on animals in Montaigne’s essays.

2.Quoted in E. Louis Backman,Religious Dances in the Christian Church and in Popular Medicine, trans. Ernest Classen (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1952), 237.

3.From an astrological chronicle for Strasbourg published in 1636 by Goldmeyer, quoted in Backman, Religious Dances, 238.

4.Paracelsus quoted in Backman, Religious Dances, 313.

5.From Annales de Sebastian Brant (1899), quoted in John Waller, A Time to Dance, a Time to Die (London: Icon Books, Ltd, 2009), 109.

6.Quoted in H. C. Erik Midelfort, A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 35.

7.Quoted in Midelfort, History of Madness, 33.

8.See Ulinka Rublack’s commentary in Hans Holbein, The Dance of Death (London: Penguin Books, 2016), 128–9.

9.Strasbourg Municipal Archives, R3, fol. 72 recto, quoted in Midelfort, History of Madness, 35.

10.Specklin’s chronicle, printed in Alfred Martin, “Geschichte der Tanzkrankheit in Deutschland”, Zeitschrift des Vereins für Volkskunde 24 (1914): 121, quoted in Midelfort, History of Madness, 36.

11.Paracelsus quoted in Backman, Religious Dances, 313.

12.“Diseases that Deprive Men of their Reason”, in Four Treatises of Theophrastus von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus, transl. and ed. C. Lilian Temkin et al. (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1996), 181–2.

13.H. C. Erik Midelfort, A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 49, quoted in John Waller, A Time to Dance, a Time to Die (London: Icon Books, Ltd, 2009), xv.

14.Waller, Time to Dance, 104.